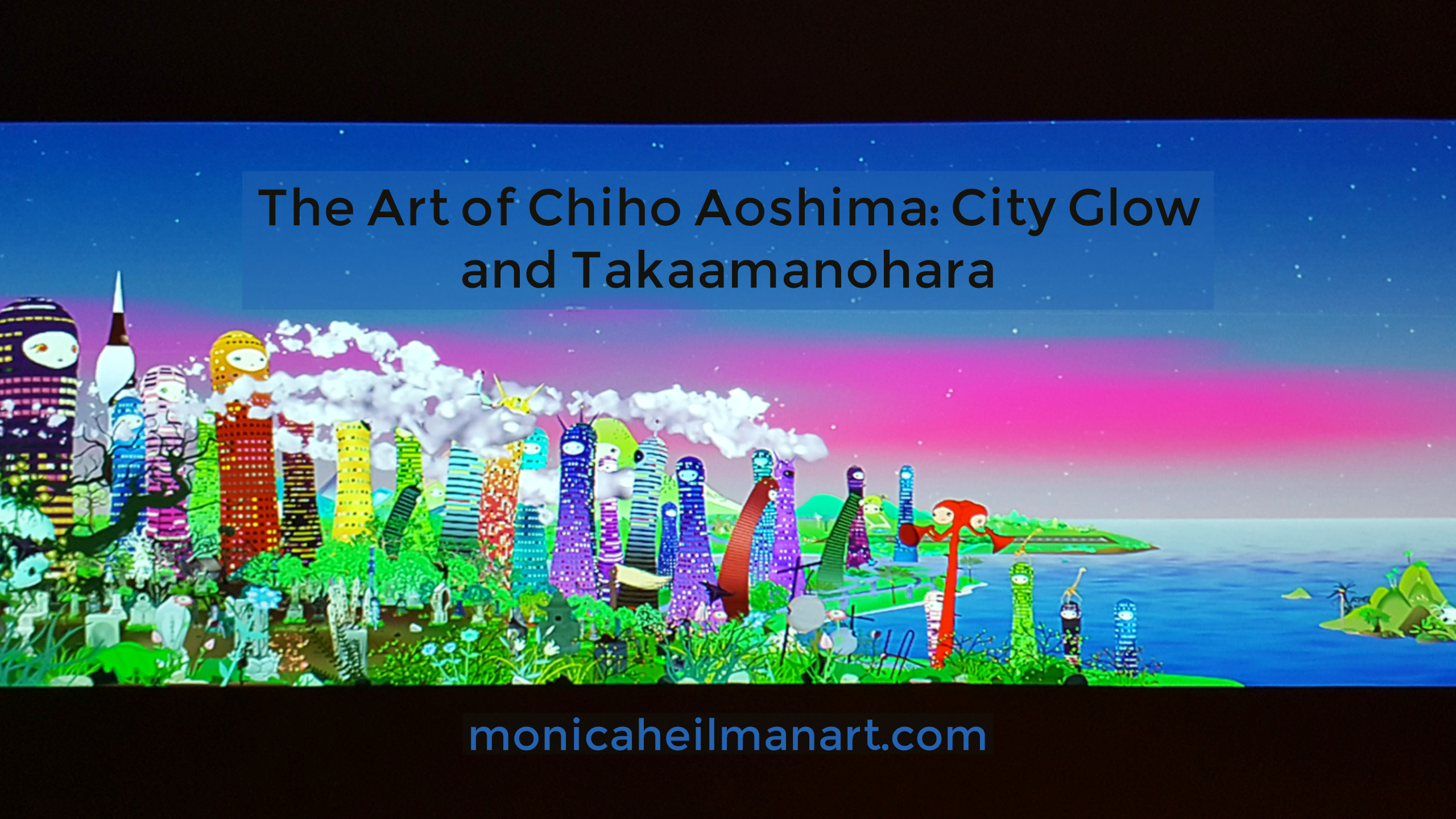

From February 3rd to April 29th, the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center is showing two video installations by Chiho Aoshima: City Glow and Takaamanohara. A Japanese pop artist with ties to traditional media and themes, Chiho Aoshima’s work is unique and strange. As one of my art idols in high school, Chiho occupies a special place in my heart.

Aoshima’s work is considered Japanese Neo-Pop. On the modern side, she draws inspiration from pop art in the vein of Takashi Murakami and anime films. You can certainly sense similarities to Hayao Miyazaki’s iconic films, but make no mistake, her work is very distinct. But naturally, Chiho Aoshima also draws from historical and cultural roots. She names ukiyo-e or 17th-century Japanese woodcut prints as a significant influence. Think that universally recognizable “Great Wave” piece by Hokusai.

Aoshima also draws heavily on Japanese Shinto mythology, with her work Takaamanohara translating to a Shinto word for “heaven” or if you want more detail, ” the plain of high heaven.”

Surprising Facts about Chiho Aoshima

Although I loved Chiho Aoshima’s art in high school, my research at the time wasn’t exactly extensive. There’s a lot I didn’t know about the artist and some of these facts might surprise you too.

- Chiho Aoshima is not a formally trained artist. She earned her degree in economics, then did a 180 and taught herself to use Adobe Illustrator.

- She was hand-chosen to be part of Takashi Murakami’s art collective, Kaikai Kiki (an easy name to remember for any Drag Race fan). Murakami is a well-known Japanese pop artist who established a “superflat” style of pop art.

- Aoshima’s work is darker than I remembered. I’ll get to this later, but both City Glow and Takaamanohara have dark undertones, one more overt than the other. It caught me off guard.

City Glow

I might have gone into the exhibit backward, but I began with City Glow, Aoshima’s older work. It was pouring rain and thundering when I entered.

The dim room carried a long projection across the wall. Sit on one of the benches or beanbags (which I love by the way) you can’t even get the entire piece in your line of vision. Stand against the back wall and there’s still too much to take in at once. This a common theme in Chiho Aoshima’s animations.

City Glow takes up close, right in front of, or even within the scenery. Leaves, flowers, and small creatures loom before you, establishing a sense of scale. You are but a tiny part of this scenery, craning your neck upward to even see the tips of blades of grass. The opening scene places you beside two enigmatic figures. You learn later that they are anthropomorphic buildings, blank-faced creatures that move much like trees in the wind.

The next piece, Takaamanohara, has similarities to City Glow, but get ready for your eyes to be even more overwhelmed.

Takaamanohara

After watching full seven minutes of City Glow, I didn’t know what was going on. I wanted to watch it again, but there wasn’t much time before the museum would be closing, and I needed to leave time for Takaamanohara. In the next room, I found longer, more expansive video projection. The size of the two could have been the same, but Takaamanohara spanned a wide landscape. Instead of being surrounded by creatures that tower over you, the viewer takes on the role of distant onlooker.

We are spectators who see natural disasters from their insignificant start to the destructive finish. But like City Glow, different elements compete for your attention. It’s Where’s Waldo? meets I Spy, but with movement and no indication of what you’re looking for. There’s a sense that you’ll never be able to take it all in, never be able to notice every detail, even when those details should be obvious, like a giant, monster-like woman scaling a building.

But you’re not alone in your spectator role. The sentient buildings sway and move and turn like slow giants to watch events as they unfold. The experience is bizarre and surreal.

After Takaamanohara, I went back for a second viewing of City Glow. It’s more immediate, the messages a little more obvious, but there are parallels. Despite the cute faces and hyper-saturated colors, there’s a definite tension and you can’t quite shake once you’ve felt it. Even after all is well again, with rainbows and fairies and sparkles, you know that if you stay long enough, the fires and monsters will return.

I don’t quite know how I feel about City Glow and Takaamanohara. But I have a nagging urge to go see them again.